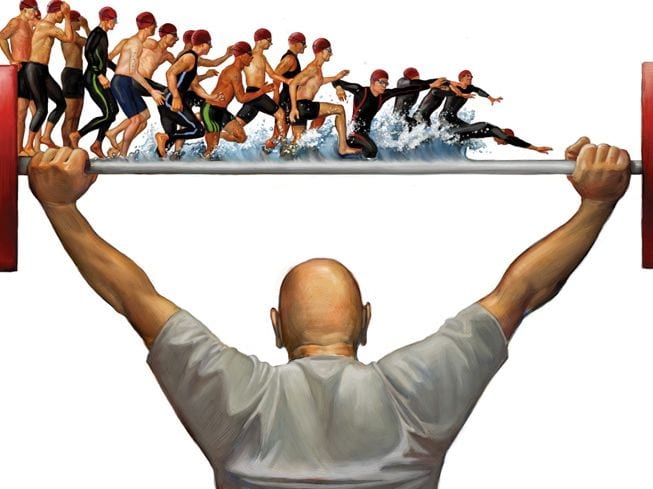

The relationship between resistance training and injury prevention.

Welcome back. If you’re a long-time club member/ first-time reader it may be worth quickly scanning your eyes across Sports Science Snippet #3. For everyone else, I know you’ve been impatiently waiting to find out how and why incorporating strength training can aid injury prevention, so without further ado let’s begin…

It has long been known that performing repetitive exercise (AKA cycling, swimming, or running) may result in muscular imbalance such as:

a) weakness and shortness and/or

b) tightness and inhibition. As a result, such imbalances often lead to:

- Less efficient or compensatory movement patterns (we use more energy than necessary when performing exercise).

- Strain, overuse and injury.

For many of us, these injuries are quite common and as such, I adapted a little table that I’ve titled, ‘Pick your muscle imbalance’.

| Table 1: Pick your muscle imbalance | |

| Postural (tendency to shortness and tighten) | Phasic (tendency to weakness and inhibition) |

| · Gastroc-soleus | · Tibilias anterior |

| · Hamstrings | · Vastus medialis (quadriceps) |

| · Iliopsoas | · Gluteus maximus, medius, and minimus |

| · Sartorius | · Long thigh adductors |

| · Pectoralis major and minor | · Rotator cuff muscles |

To explain this table further, muscles that are used frequently can shorten and become dominant in a motor pattern and the antagonist muscle (opposite muscle) may become inhibited resulting in muscle imbalance. A great example of this is the relationship between our hip flexors (iliopsoas) and our deep abdominals and primary hip extensor (gluteus maximus). In running, due to repetitive use, our hip flexors can become tight and short. Comparatively, although our gluteus maximus should act as one of the major muscles propelling us forward in the run, it can become elongated and weak. Inhibition of the gluteus maximus may result in inadequate stabilisation of the lumbar spine, with lower back pain or tight ITB often been a resulting symptom.

Resistance training helps with muscles imbalances by strengthening our weaker muscles. As a result, our system can contract in a coordinated manner with sufficient muscular control. Ultimately, this results in optimal length-tension relationships in addition to optimal force-coupling of muscles. Further, as previously discussed, improvements in strength ultimately lead to improvements in performance.

However, just like we do in our endurance sessions (swim, bike, run) it is also imperative to progress our resistance training. As our muscles adapt to our resistance program, we need to overload them to continue building muscle strength and mass. This progressive overload principle can be applied in a number ways, such as increasing the resistance or increasing the sets. I like to liken this principle back to the old, ‘My physio gave me exercises and I stopped doing them once I felt better,’ example. If your exercises from your physiotherapist begin to feel quite easy that is probably a sign that you’re a) on your way to getting over your injury and b) you should get the progression exercise to continue to improve your strength so you don’t get re-injured.

Whilst I have not mentioned it in this article, the role that flexibility training plays in muscles imbalances is equally important and should not be overlooked. This will be touched on in a future article.

A couple of notes:

- You’re a rare and potentially flawless human being if your muscles are perfectly balanced. Whilst strength training can aid in injury prevention, we are still mere mortals and the shape of our bodies plays an important role in the way our muscles develop. For example, due to a wider pelvis females are automatically predisposed to greater risk of ACL injuries.

- If you’re beginning a resistance training program PLEASE receive professional instruction in proper resistance-training techniques.

Discover more from Tri Alliance Triathlon Community

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.